Mindy Chen-Wishart

Please tell us a bit about your background, ie where you came from, your education, your current family situation.

My family have been in Taiwan for many generations. My grandfather was a truck driver and my father was the first in his family (of 10 children) to attend university. He did so only because he used to carry the bag of a schoolfriend who had polio; his friend went to university and so he followed. I was born in a small town called Luodong and moved to Taipei when my father started teaching there. We thought him impossibly glamorous when he attended two Olympic games as coach of the Taiwan gymnastics team. I did not want to immigrate when I was ten, I wanted to stay with my grandmother. There were no other Taiwanese immigrants in the South Island, and I can only thank my parents I have three sisters who share my history. Our parents promised us a horse; we’re still waiting. I am so grateful to NZ for financially supporting me while educating me free of charge. This generation must go into significant debt to attend university. My youngest son (of three) started university this year. I am finally an empty nester.

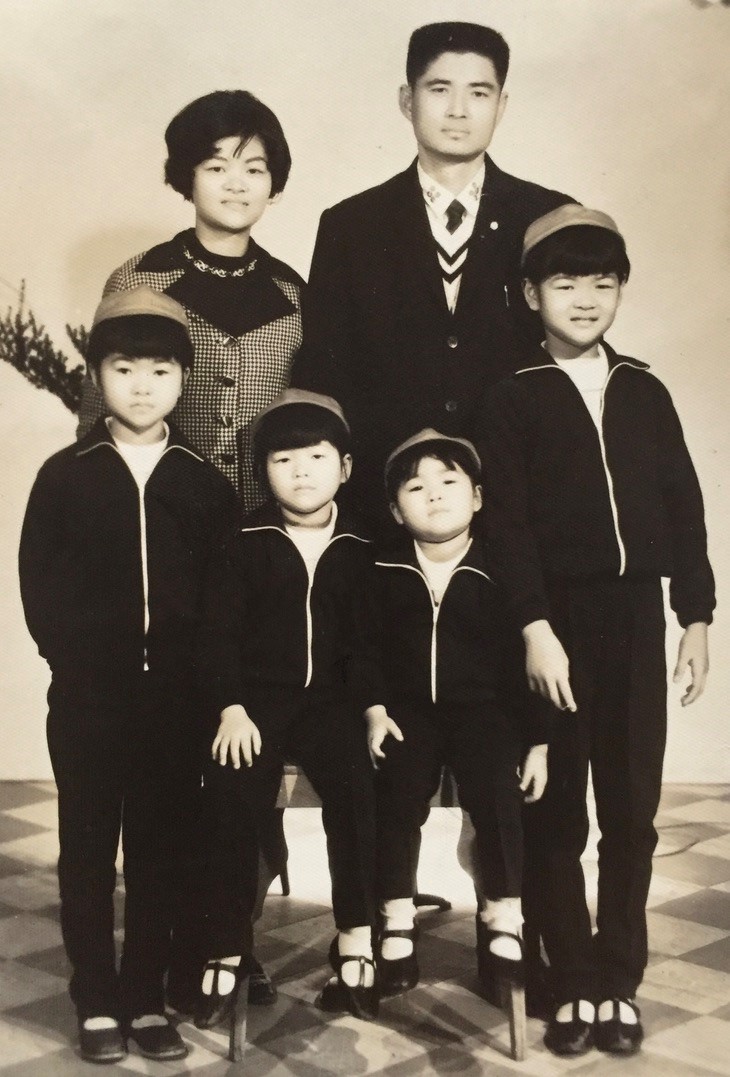

Mindy and her family on leaving Taiwan. Mindy is far left.

At Otago University, I started in science and drifted into history and law which looked and were more fun. On graduation, and after a rather sexist job interview (“what is your husband’s five-year plan?”, “we’ve had problems with women hires, what do you say?”), I consulted my professor at Otago University who suggested I become an academic. This seemed a good alternative to that one single law vacancy in Dunedin at the time. It never occurred to me to move! When my sons were little, they thought I was no good at schoolwork because I was still at school. I love my job. It’s an honour to be paid to teach, study and write my truth. When my sons (then teenagers) discovered that my in-laws disapproved of me as a ‘working mother’, I asked whether they thought I should stay at home. They looked panicked as one said to the others: “OMG! Imagine having all of Mum’s attention!”

Mindy Chen-Wishart and her children

I had two small boys, aged three and new-born, and so intended to spend my first sabbatical at home (of course!). A senior colleague at Otago (former law fellow at New, College Peter Skegg) thought otherwise and shoved an application for the three-year Rhodes Visiting Research Fellowship under my nose, insisting that I apply. “Errr, no. It’s for post-docs; it’s in any subject (not just law); it’s for NZ, Australia, Singapore, HK and Malaysia; and it’s in Oxford! No. No!” Well, I was surprised and intimidated to get an invitation to interview, lost for words when the principal of the college told me that having two children would be awkward and “what do you plan to do with them if you get the Fellowship?” and appalled when UK immigration said that a woman could not bring in a “dependent male spouse”.

I found my time in Oxford a struggle. We were poor (down to milk tokens one week), I had post-natal depression and I felt inadequate for ‘Oxford’. So, when my husband said he’d like to stay longer now that he had a job, I was horrified. I devised a cunning plan: to show willing, apply for an impossible post, not get shortlisted, and say, ‘see, I tried, now let’s go home to NZ’. The plan went horribly wrong. And here I am still, my sons having long ago vetoed any move.

What are your research interests and why have you chosen those particular areas?

I have taught a lot of subjects over the years, including restitution with the great Peter Birks for eight years. My research now focuses on all things contract. I started with doctrinal law which is foundational. When I got bored with that, I started attending the classes in Philosophical Foundations of the Common Law, and the wonderful John Gardner kindly invited me onto the team. Latterly, I got to teach it with Hugh Collins and leant much from him (couldn’t believe it, I had a crush on him when I first read his contract law book in 1986 NZ). I also got involved in some European comparative contract law projects and more recently, quite accidentally, I started a six-book project on the contract laws of 14 Asian jurisdictions. I love contract law. Human beings are weak (furless, fangless and clawless) yet we are the most dominant species on Earth. Other species make and use tools, but they don’t coordinate and cooperate to the high level that human beings do - a significant form of this is via the institution of contract. Contract law gives a partial but important answer to the perennial question: how should we treat one another?

Why did you want to take on the role of Dean?

I was on sabbatical in NZ last November when I received a call asking if I would throw my hat into the ring. “Nope” said the voice in my head. After a four-year stint as Associate Dean of Taught Graduates, I had decided to eschew administration in favour of my research projects. But Oxford is special; it is my intellectual home and, having started with a colonial chip on my shoulder, I am a believer in its slightly chaotic system that generates creativity, commitment and the highest levels of research and teaching. It is not beyond tweaking here and there to improve the professional lives of colleagues and the experience of students. So, I take my turn to serve and I will no doubt learn a lot.

What do you see as the challenges the Faculty faces over the next 2 – 3 years?

I accepted the Deanship in a different world. COVID19 has upended the normal modus operandi of the Faculty. It’s a difficult, stressful and even distressing time for people: academics, administrators and librarians are working harder than ever to deliver teaching that is, nevertheless, not the ‘Oxford’ experience that students hoped for. How long will this go on for? How many waves will there be? Will a vaccine be successfully tested and rolled out? How long is this piece of string? We need to be agile and creative to provide as much support and stability as possible.

What do you hope to achieve in your role as Dean?

Our core mission is world-class teaching and research. To do that, we need to look after two things. First, money isn’t everything but it supports our aims and no money clips our wings. So, we have to be really creative but careful in that department. Second and most important is our people. The Law Faculty should be a place where people are noticed, supported, respected and appreciated; a place where people have a sense of community and of our common purpose. I will be focussing on these two irreducible minima.

What charity do you support and why?

One-2-One, which operates in Cambodia, Myanmar, Timor Leste, Laos and Vietnam, and meets dental, medical, educational, vocational and physical needs for the poorest of the poor. It was started by my sister Dr Annie Chen-Green who I much admire. She is tough and utterly fearless. She flows around the numerous obstacles she encounters like water. In the current pandemic, hers is one of the last charities still operating, and it is doing so at full-tilt because she empowers locals so that it can run without her.

Do you have any other accomplishments besides your academic career?

I play the violin badly (unlike most parents, mine forbade practicing because of the noise); I was the national age-group champion in backstroke and butterfly (but hardly anyone could swim in Taiwan); I cooked dinner for the whole family for a year when I was 12 (the food was quite decent by the end); I made my own wedding dress (my grandmother felt so sorry for me (only poor people do that) that she sent a big horrendous lacy meringue number from Taiwan that I had to wear); I draw portraits and wanted to be an artist but was made to do Latin (never mind, my son is an artist and I have retirement); I did an interpretive dance at church (dead silence and no one gave me eye-contact afterwards); oh, and I worked as a life saver at a public swimming pool (disappointingly, no one needed saving).